Pursuing Those Emotional Questions

On Friday, November 9th, we welcomed a trio of writers to campus for another reading. This time, James Scott, faculty member and author of The Kept, Sean Prentiss, faculty member and author of Finding Abbey: A Search for Edward Abbey and His Hidden Desert Grave, and Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, author of The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir each read us excerpts of their work.

A surprise snow shower started just before our evening began. Through the windows of Café Anna, we could see the flurries swirl across the campus green, settling on the fountain that has been drained in anticipation of our dropping temperatures. It all served as another poignant backdrop to the words our readers shared with us.

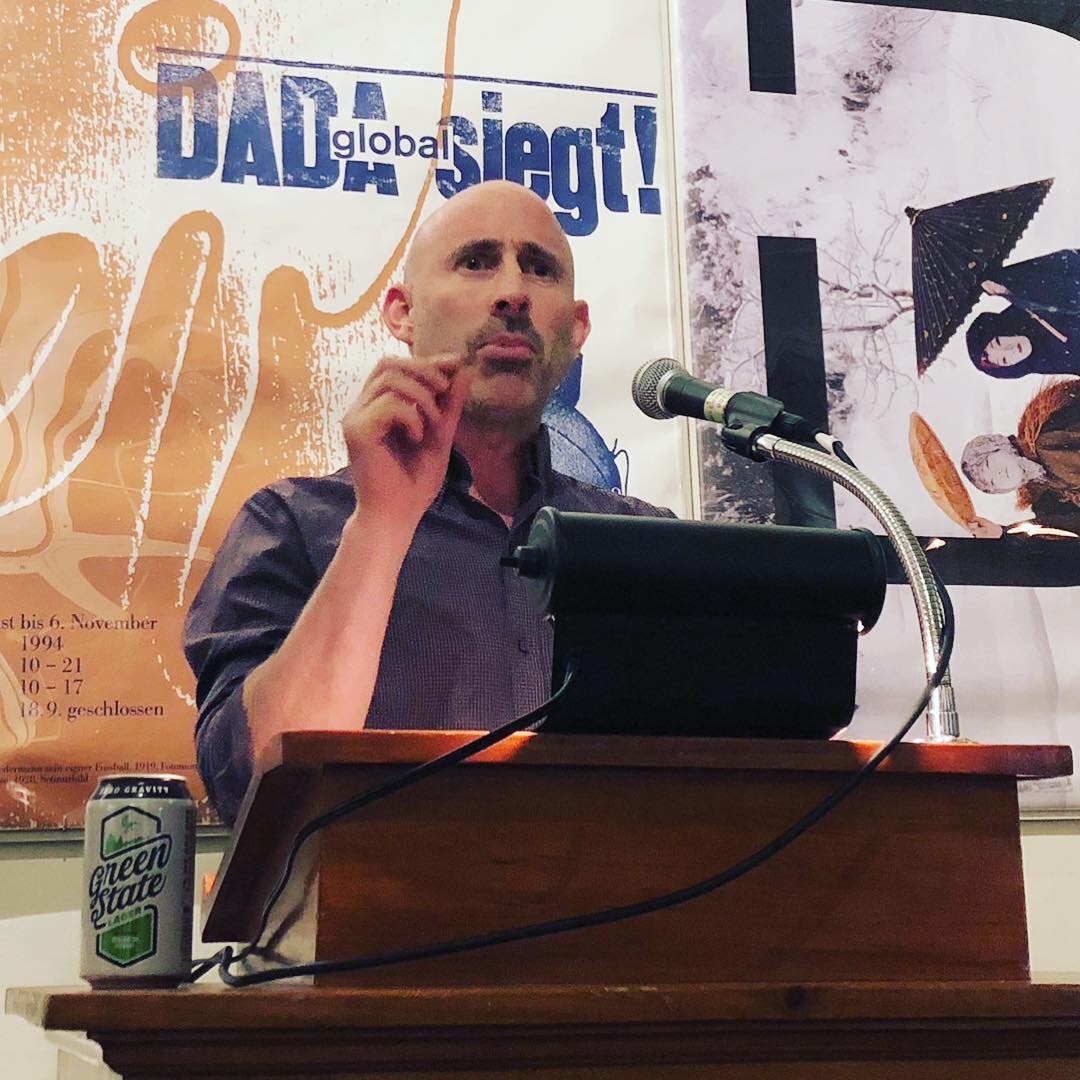

“We all started a class here with [James Scott] this week, and yesterday,” Mariah Hopkins, ’19 began candidly, “James taught us that there is an emotional question behind every piece of writing…and the emotional question behind this piece of writing,” she said, gesturing to the introduction she had written for Scott, her thesis advisor, “is how to do James and his work justice in such a short paragraph.”

After detailing his recent literary successes, Mariah welcomed Scott to the podium.

“I love writing because writing is like having a daydream—you can go wherever you want,” Scott began, recalling an exchange he had had with a friend who works with fourth-graders, one of whom offered the insight. After wondering aloud what the appropriate gif to send in response to such a declaration might be, he continued: “It made me think about what I’m working on now, and that it really started with some daydreams that occurred here in Vermont.”

As you may imagine, all Vermonters—natural-born or recent converts—blushed to ourselves in the audience. There’s simply no way around it: Vermont is a pretty dreamy place. It’s always nice to get a little validation, isn’t it?

James Scott then transitioned into reading the prologue for his current work-in-progress. I won’t reveal too much, except to say that it’s eerie, cold, and wet—and desperately mysterious. If that’s not an enticing combination of adjectives, I don’t know what is.

“At the end of my first year here at VCFA, every one of my classmates seemed to know what they were working on for their thesis project. I did not.” Mike Demyan began in introduction of our next reader, Sean Prentiss. He went on to confess that an essay he wrote in Prentiss’ nature and environmental class became the seed to what his thesis has evolved to today. He related Prentiss’ self-described relentless work ethic, prevalent talent in the creative non-fiction scene, and expansion into other areas of the writing world—a perfect example of the cross-genre exploration we students are expected to delve into ourselves during our time here.

“Every once in a while, I enter a fugue state and write a short story,” Prentiss started. “And by ‘once in a while,’ I mean like every third year. I know nothing about fiction…and I call this the dark art of fiction.”

Demonstrating his flexibility (even in the dark arts!) he went on to read a piece of short fiction about the intersection of young love and math. He raced through the story at breakneck speed, describing the bizarre conditions of infatuation and equations (and axioms, quadratics, and algebra) with the perfect frenzied feel, entirely evocative of what attraction feels like.

Alex Marzano-Lesnevich began with a disclaimer.

Because their work, The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir is non-fiction, some of which pertains to the murder of a six-year-old in Louisiana in 1992, Marzano-Lesnevich was artfully direct about their sources and their opinions in the process of writing their book. In haunting narration, Marzano-Lesnevich continued, detailing the conditions of the boy’s murder.

“I trained as a lawyer before doing an MFA, and when I was in my law program, I took a job in Louisiana, helping to defend men accused of murder,” they said after finishing the difficult passage. “Now, I am the child of two lawyers. I grew up talking about the Constitution over the dinner table. I remember the moment when I learned about the death penalty. I was horrified by it—felt right away that it was wrong. I have since learned that that is not a formative memory for most American schoolchildren, but it was for me.”

Before finishing their reading with a section from the memoir portion of their book that is woven into the account of the murder and its consequences, Marzano-Lesnevich paused, allowing us to step into their thought-process in going about this project. Needless to say, the subject-matter was stark and disturbing, but their self-reflective line of questioning was stunningly relatable: “Is who we are determined by the past,” they asked us, “or is who we are determined by what we believe?”

Photo credits to Bianca Viñas. Adidas shoes | Autres