Lewis “Buddy” Nordan, “Owls”

Lewis Nordan, whose nickname was “Buddy,” stood in the same Southern Gothic cathedral as Faulkner and O’Connor. Over the course of his life he wrote four novels, three short story collections, and one “fictional memoir” before his death in 2012. Nordan played with expectations in unique ways: his uniqueness was magical realism by way of small-town Mississippi, deep in the Delta, his native home. Lyrical tales of singing llamas and ghosts and a dead boy’s sentient eyeball—a reference to Emmett Till’s murder, which occurred when Nordan was a child and haunted his entire life. His stories contained blatant falsehoods, shaky memories, and unreliable narrators.

“At the house party of Southern fiction, full of death-dealers, drinkers, and unshaven folks behaving badly,” says M.O. Walsh, writing in the Oxford American, “Lewis Nordan stands alone in the yard, like a boy in a bright-blue suit his mother picked out for him. Yet his is the same haunted South as ours. He’s witnessed the same troubles, fought the same demons. Through his eyes, though, the South is transformed. His swamp is full of mermaids. His trashy neighbors sing arias in the cabbage patches. His depressed and alcoholic father is magic. His heart is open and honest and shredded and, thank God, he was willing to show it to us.”

“Nordan’s acknowledgment of me as a writer meant the world to me,” said Julianna Baggott, who teaches our Forms class. Baggott first met Nordan at a reading when she was a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro. In her words, he was the first writer to take her seriously. “He was the first person—upon meeting me and hearing my name—to say, ‘ah, Julianna Baggott, I’ve read your work.’ That sentence alone changed my life.”

In our Forms class we listened to a reading of Nordan’s short story, Owls. It is the final story in Nordan’s collection Music of the Swamp, a novel comprised of separate stories about its main character, the boy Sugar Mecklin. You can read an excerpt here.

“Once when I was a small boy of ten or eleven,” it begins, “I was traveling late at night with my father on a narrow country road. I had been counting the number of beers he drank that night, nine or ten of them, and I was anxious about his driving.”

We first listen to it hypnotized by Nordan’s spare language, a minimal sensibility that conveys so much: a porch light burned into our mind, the red eyes of rabbits, owls circling overhead. We believe everything because we go into the story with so much trust for the narrator—and also because the steady voice of the audio leaves us with no time to pause, to think things over.

Then, Nordan’s narrator (with the help of a lady friend) forces us to question everything. Do owls circle en masse? Are rabbits’ eyes red?

Did the whole thing happen?

“Was your father magic?” the unnamed woman asks.

“I wanted him to be.”

Nordan’s stories are dark and pinpricked with glimpses of magic. He has said before that his stories are about his father wanting to love him. After spending the entire story reinventing his past, he concludes Owls with a line as moving as it is transcendent: “there is great pain in all love, but we don’t care, it’s worth it.”

At that reading twenty years ago, something unusual happened—something clicked for Baggott. “At the end of the story,” said Baggott, “Nordan’s throat went tight. He had to take a moment; he was choked up. It was amazing to me to see a writer move by some memory coming alive in a moment, unexpected.

“It surprised me that the story was so authentic, and ran so deep. It’s important to be vulnerable, especially in front of students who need that vulnerability modeled. I’m thankful for his honesty.”

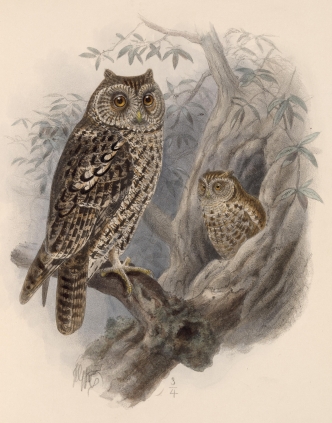

(Artwork: Megascops trichopsis (Whiskered Screech Owl), John Gerrard Keulemans, 1902)Nike footwear | NIKE HOMME

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!