Riots, Rattlesnakes, and Rare Beasts

How time flies: we’re already at our last reading of the semester! And for this one, three extremely accomplished guests brought their finest work.

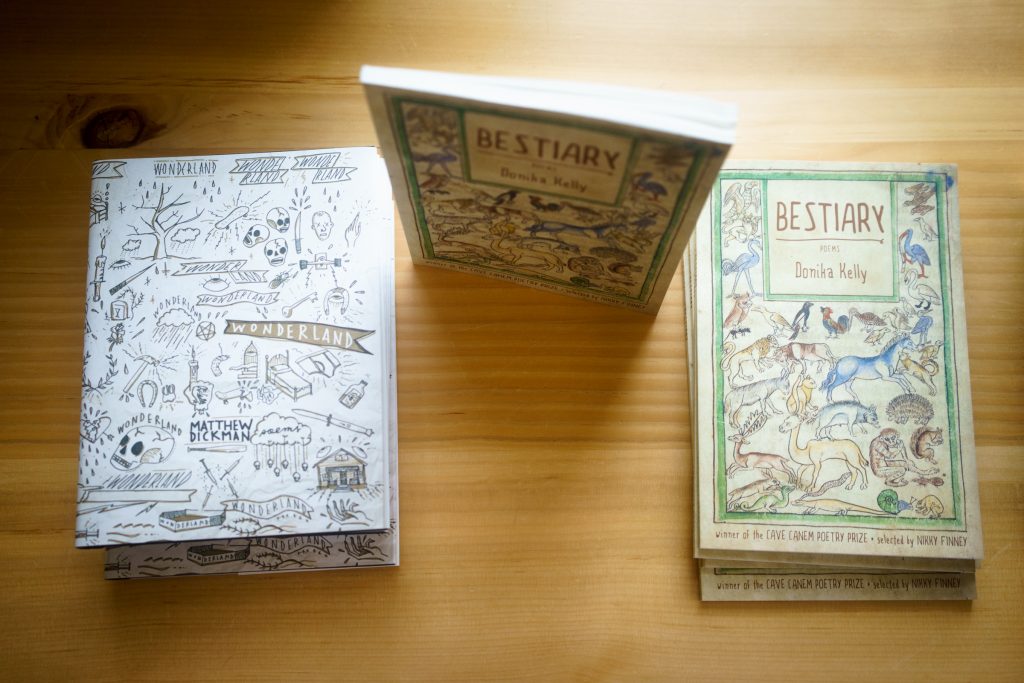

First up, Matthew Dickman—Oregon Book Award winner and Guggenheim Fellow, reading from his latest collection of poetry, Wonderland. It is one of the three books you should read before you perish from this earth. It is a collection “charged with raw beauty and heartbreak,” said fellow poet and MFA candidate Jad Yassine, introducing him. “He talks about poetry like he’s just discovered how great it is.”

“I promised certain family members I wouldn’t embarrass myself for saying ridiculous shit,” said Dickman just before he began, adding, “but you know, it’s unavoidable.”

In describing his childhood, Dickman writes with spare and honest language: in one poem, “Transubstantiation,” he describes a trip to the supermarket and an encounter with a strange man. In “The Order of Things,” he questions his superiors (nuns at a Catholic school, aka “Gods’ adults”) and their brutal punishments. In “Teenage Riot” he talks of “flipping off cops and skinheads,” doing teenage stuff, and eventually swirling down into acts of violence. He read: “The man, startled, sat down, right there on the asphalt, / right in the middle of his new consciousness, / kind of looking around.”

It ends without exaggeration—something Dickman has drilled into our minds through his craft course. “Don’t exaggerate,” he told us. When writing about lived (and dramatic) events, his message is: do not romanticize, stay anchored in the occurrence of violence.

Melissa Febos read next. Febos, who in a TED Talk extolls the virtues of revealing your secrets, wrote the 2010 memoir Whip Smart, where she reveals her secret life as a dominatrix. Last year, her book Abandon Me debuted: a collection of essays related to her search for her bioloical father. She teaches at Monmouth University and has earned fellowships from MacDowell Colony as well as awards from Prairie Schooner.

To give us a preview of what she would read, she told a story: before a recent reading in another city, she asked a friend, “should I read an essay about how much I love hickies or how much I cried as a kid?”

“Is Portland more of a hickie city or a crying city?” her friend responded.

In unison, the two decided: “crying.”

That night, at the podium, she observed: “colleges are hotbeds of both hickies and crying.”

The essay she read concerned both. In it, Febos and a lover journey to West Texas, listen to the train horns echo across the desert, and stop at the World’s Largest Rattlesnake Exhibit—which is a real place. She read, “When a human makes such a sound, it expresses only a few things: Terrible grief, earth-shattering climax, triumph, or pain…that kind of sound is all body, all heart, out of mind.”

Then she stopped. “How do you guys feel about emotional needs?”

“Yes,” said Donika. Matthew gave a thumbs up.

“Then this is not for you.”

She continued with the essay.

Donika Kelly was our final reader that evening. Kelly, described by the New York Times as “a descendant of Sylvia Plath by way of the wintry Louise Glück,” just debuted with Gray Wolf Press her first-ever collection of poetry: Bestiary. In the slim volume, she encounters wild and mythical beasts alike: whales and centaurs, hermit thrushes and chimeras. (Hey, Everyday Chimeras!)

Before reading “Love Poem: Chimera,” she described the creature: “Body of a lion, tail of a snake. Middle of the back is a goat’s head. Just so we’re on the same page.” Then, she read:

What clamor

we made in the birthing. What hiss and rumble

at the splitting, at the horns and beard,

at the glottal beat. What bridges our back.

What strong neck, what bright eye. What menagerie

are we. What we’re made of ourselves.

In Kelly’s poetry, Perseus cuts off Medusa’s head; from the wound springs a horse with wings, “foaled, fully grown, from my mother’s neck…my first cry, a beating of wings.” With a hint of sarcasm, Kelly calls out the misogyny that ancient Greeks never had to answer for, writing:

What beast

will your blade free next? What call will you loose

from another woman’s throat?

Kelly describes her family, her brothers, her father as a winged boar, her childhood in the 1990s when “her parents still loved one another,” and of the summer in 2011 when she was in Nashville at the same time a 17-year old brood of cicadas emerged from their hidden places, their little exoskeletons clinging to everything in sight.

This is what you pay attention to when you’re a poet, or when you’re in love, or both.